Rangoon, Burma 1880

Campbell Hart was the father of Féo Clarke and David Hart. Born on the 24th February, 1880, he was baptised Alexander John Campbell. It was always known within the family that he had been born in Rangoon, the then capital of British Burma, but it was also a mystery why he had been born there. Family lore suggested that his father, Alexander, may have been a Cornish marine engineer, or even a ship’s master operating in the Far East, but there were no facts to corroborate this suggestion.

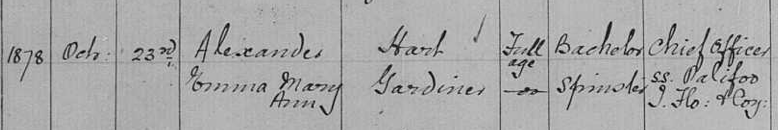

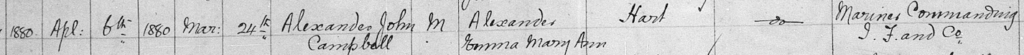

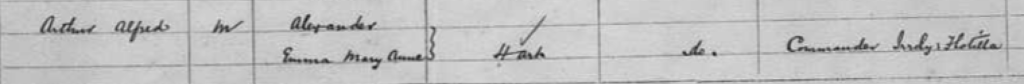

Fortunately the colonial authorities in British India were meticulous in their record keeping and I was able to come across Campbell’s birth and baptism certificates through an online search. It is from his baptism certificate1, where it is recorded that he was born to Alexander and Emma Hart (née Gardiner), we gather the first clue. From both this document and from his father’s marriage certificate2 we learn that Alexander had been a “Mariner Commanding J.F & Co” and “First Officer on the ss Palifoo, J Ho & Co.” These enticing hints led me to research the historical context of Campbell’s birth.

Burma was an exotic, mysterious kingdom in the early 1800s, on the one hand presenting an image of a peaceful, agrarian, self sufficient country with a contented and meditative Buddhist population while on the other dominated by a despotic and militaristic king, Pagan Min, who ruled with a capricious disregard both for his close relatives, whom he regularly butchered, or for international treaties, which he carelessly abrogated.

But it was not the romance of this exotic land or the seductive tranquility of the golden tipped pagodas rising from the banks of the Irrawaddy that attracted the British into Burma, but rather the seemingly limitless forests of teak that were growing alongside this vast navigable waterway which bisected the kingdom of Burma for over a thousand miles.

The burgeoning trade of the expanding British Empire and the associated increase in shipping was rapidly depleting the British owned forests around the world. The oak forests of Ireland had already been denuded by the need for ships during the Napoleonic wars and the colonial settlers of New Zealand were making valiant efforts to haul the last of thousand year old Kauri trees from their mountain stands to the sawmills of the coast. It was not surprising therefore that the British shipbuilders, mariners and merchants began to lobby Parliament for a greater share in the country’s wealth. They had after all been eyeing the virgin forests of teak that lined the banks of the Irrawaddy river from Rangoon to Mandalay with more than covetous eyes.

The British had gained control of the Burmese coastline, which included the major strategic ports, as a result of the first Anglo Burmese War in 1827. This had been fought in order to protect the East India Company’s sphere of influence from incursions by the King of Burma along its North East frontier in what is Bangladesh today, which the East India Company considered to be its own bailiwick. The cost of protecting Calcutta and East Bengal from this perceived Burmese threat was at the expense of some 15,000 lives, but nonetheless evidently a worthwhile investment as it came at a far greater cost to King Pagan Min, who was forced to cede his coastline, pay a crippling fine for having caused the war and agree a one sided trade deal. To cap his humiliation he then lost his throne to his half brother who appeared more amenable to agreeing terms with the British. And so ended the First Anglo Burmese war.

Of course there were other geopolitical incentives for the British to take control of the rest of Burma, not least the irritating influence of the French who were cosying up to the king in pursuit of their own imperial ambitions in South East Asia and also the prospect of an overland trade route into China linking the already vast British held territories of India with a market of 300 million consumers. The British always maintained that they had no militaristic ambitions for territory, only the peaceful pursuit of free trade, if only their trading partners would accept their terms. Burma offered an unrivalled opportunity, not only for the export of such valuable commodities as teak and rice, but also for opening up new markets for the finished products of British industrialists and manufacturers.

The annexation of lands rather than conquest was a useful expedient which had been carefully honed by the British in India over the previous hundred years, resulting in the domination of the entire country by 1860. I say British, but the British Government could be excused for not having played a direct hand in it, as the command and control structure was entirely that of the East India Company, a private enterprise of City of London merchants to whom both the ruling Monarch and the British Parliament had conceded both the right to rule and the privilege to profit. By a gradual process of divide and rule the East India Company subverted Mughal sovereignty, supporting rival princes of the disintegrating dynasty with East India Company regiments until by 1856 the last Emperor, King Zafar, was merely a puppet of the East India Company in his capital, Delhi. Following the fall of Delhi after the suppression of the Indian Mutiny, the king was deposed and spent the remainder of his life in exile in Rangoon.

The tactic was simple following this 10 point plan:

- Inveigle your way into a host country by means of establishing a trading post.

- Negotiate rights for your merchants and shipping.

- Offer the protection of the British legal system for the resident colonists.

- Protect your colonists with a private army recruited from the host nation.

- Provide your host, or his enemy, the protection of your mercenary army, at a price.

- Engineer a situation where your host rescinds a treaty thus providing a “casus belli”.

- Seize his land in reprisal and defeat his forces with superior numbers and technology.

- Demand: a) Surrender b) Reparations to cover cost of war c) A new one sided treaty.

- Assume administrative control of former host’s territory.

- Export the rich natural resources while importing British manufactured goods. QED.

Variations of this template were replicated in successive wars of the Victorian era, the apparently belligerent host country being forced to cede its territory to its self righteously outraged guest. It took only a minor diplomatic incident, on a flimsy pretext, to justify a display of gunboat diplomacy against the Burmese. While the response to the Burmese provocation was both swift and decisive it was clearly premeditated, as the planning of the storming of Rangoon, and the subsequent subjugation of Lower Burma, had been slow, calculated and meticulous.

This invasion involved four steamships of the East India Company and some towed hulks that had been gutted and converted as troop carriers and a flotilla of barges that were built in Calcutta and as a nineteenth century precursor to IKEA, dismantled and freighted as flat pack boats to be re-assembled in Moulein harbour on arrival in Burma. The entire flotilla of steamships, hulks and “flats” as they were called made their way up the Irrawaddy with their regiments of East India Company native infantry for the storming of Rangoon and the subsequent annexation of the entire area of lower Burma, which then became known as British Burma and with it came the end of the Second Anglo Burma war.

Following the successful occupation of Rangoon and the subsequent annexation of lower Burma the steamships and flats were offered for sale, with a sweetener of a concession to run the mail packet to Calcutta. A public company was floated to purchase and run them, providing conveyance of both cargos and passengers between Rangoon and Mandalay. This company became to be known as The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company.

The life of Campbell’s father Alexander, however, still remained something of a mystery to me until I discovered his marriage cert to Emma Mary Ann Gardiner in 1878 in Rangoon, British Burma. The certificate contained some clues as to what sort of trade he was engaged in stating that he was the Chief Officer of the what appeared to be the ss. “Palifoo”.

I was unable to find a vessel by the name of SS Palifoo in the Lloyds Register, nor could I find find any trace of a shipping company by the name of J Ho & Co.

Even the Baptism Cert of his firstborn, Alexander John Campbell is not much more enlightening, although it does eliminate the “Ho” in favour of the initial “F” and we see that Alexander is promoted to Mariner Commanding J. F & Co.

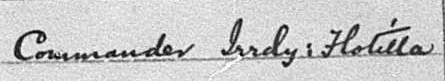

It is not until the birth of his second son, Arthur Alfred, that the mystery is revealed and we see his profession listed as Commander Irrdy: Flotilla.3

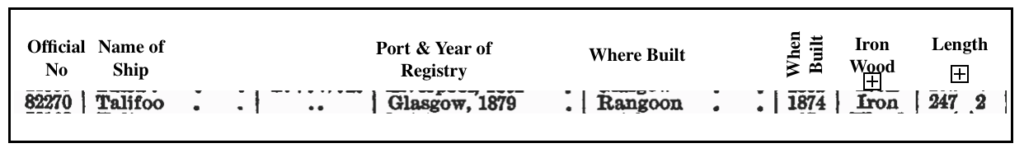

It did not take a great leap of imagination to connect this abbreviation with the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company and a subsequent search of records at Greenwich Maritime Museum revealed lists of vessels associated with the IFC including the SS Talifoo – and tantalisingly they have a box of photos in their archives which includes several of the Talifoo – maybe also of its Commander?4

A quick look on Lloyds Register5 revealed the following information for the vessel:

Campbell’s father, Alexander, was clearly a man of his time, taking employment in his chosen trade where it was offered in a stable and expanding industry in Rangoon with great prospects for the future.

Rangoon – British Burma 1880s

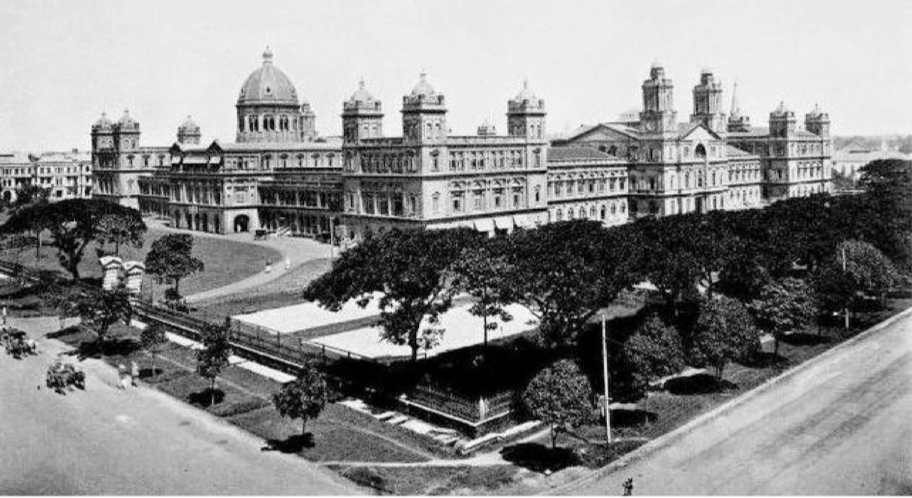

One could be forgiven for thinking of Rangoon as a remote frontier outpost of the Eastern British Empire, but that would be to ignore the extent of the colonial ambition for the city and this is best reflected in the sheer scale of its architecture. The annexation of these lands was not some temporary little arrangement as was evidenced by the immediate transposition of the British Burmese capital upriver from Moulmein to Rangoon. The commercially minded arrivistas demolishing the pagodas, stupas, shrines and temples along its waterfront, erecting piers, wharves and slipways in their stead, removing the random scatter of streets and shacks to establish a modern city on a gridiron layout.

By the turn of the century Rangoon was a rival to any city within the British Empire and with public services and an infrastructure that were reputed to be on a par with London and an architecture and administration designed to promote power and prestige and showcase a world girdling Empire in pursuit of free trade and the implementation of British civilisation.

It was at the start of his promising career as a Master Mariner that Alexander met and married Emma Mary Ann Gardiner, Campbell’s mother. Emma was born in Clifton, Bristol and her father, John, was also a Master Mariner,6 commanding sailing ships between Scotland7 and the Far East.

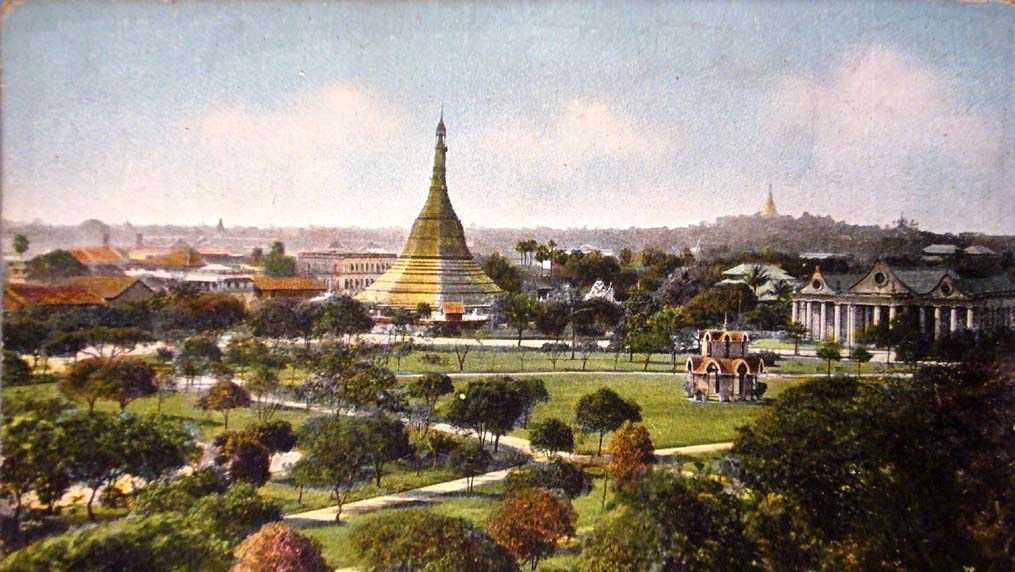

Campbell was baptised two weeks after his birth, on the 6th April 1880, in the same church where his parents had married some eighteen months earlier. The newly built Anglican church of The Holy Trinity stood somewhat incongruously amongst the ancient Buddhist temples of Rangoon, and in particular juxtaposed against the iconic gilded stupa of the Shwendagon Pagoda.

Schwedagon Pagoda

Holy Trinity Church

Sources:

1. Campbell Hart Birth Certificate: India, Select Births and Baptisms, 1786-1947

2. Alexander Hart & Emma Gardiner Marriage Certificate: India, Select Marriages, 1792-1948

3. Arthur Alfred Hart Birth Certificate: India, Select Births and Baptisms, 1786-1947

4. Royal Museums Greenwich, Collections: ALB0295, ALB0290

5. Lloyds Register: Appropriation Books, Official Number 82270

6. John Gardiner Master’s Certificate: UK and Ireland Masters and Mates Certificates, 1850 – 1927

7. Maritime History Archive, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Crew Agreements for John Gardiner

Background reading:

Irrawaddy Flotilla by Alister McCrae & Alan Prentice

The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi 1857 by William Dalrymple

The Honourable Company: History of the East India Company by John Keay

The Pacification of Burma By Sir Charles Crosthwaite, KCSI. (Archive.org)

Pegu, The Second Burmese War by William F.B. Laurie (Google Books)

Useful Websites:

FIBIS & Fibiwiki, Friends of British in India Society: https://www.fibis.org

Researching Ancestry: ancestry.com (Record transcripts and Family Tree)

Researching Ancestry: findmypast.com (Original document scans)

Researching Ships & Captains: crewlist.org.uk