A Call to Arms

Large crowds lined the wharves at Southampton Dock on Easter Saturday 1900, cheering and singing as the SS Canada moved slowly away from the quay, only to slide up onto a mudbank on the falling tide. If this was an ill omen for the 1,500 or so men from a variety of Battalions and thirty women from the Army Service Nursing Reserve, no one displayed any anxiety as the singing continued on board with renditions of popular patriotic songs. With the turn of the tide the Canada finally rose free of the mud and steamed out into Southampton Water bound for Cape Town, 7,500 miles away. Campbell was off to war!

The Atlantic swells set up an irregular rolling motion on board and many of the company became seasick causing the cancellation of the Easter Sunday church parade. For Campbell the voyage brought back memories of his last time at sea, when as a twelve year old he sailed aboard the cargo ship the SS Menalaus from Singapore to London. Then he was one of only four passengers and enjoyed the attention of officers and crew. This time he was part of a military operation, under orders, behaving with strict discipline. For both adventures the outcomes were uncertain, but if he survived this one, it could be his ticket back to Singapore where his mother Emma and sisters Dorothy, Daisy Emmie and Winnifred lived.

Campbell threw himself into the routine and discipline of life on board. Reveille was at 6.00am and after parade the mornings were spent in a variety of training exercises: signalling classes, physical drills and lectures on scouting and horse management as well as musketry practice firing at barrels and boxes thrown overboard. The afternoons were spent on sports – blindfold boxing a favourite – and inter battalion games such as tug o’ war in which Campbell’s battalion the 20th took delight in besting the Irish Yeomanry. Led by Captain Lord Longford1 his battalion was made up largely of volunteer Irish masters of foxhounds and landed protestant gentry.

The last few months had been a heady time for Campbell, as indeed it had been for the public at large. Whipped up into a patriotic fervour by the newly published titles of the popular press – the Daily Mail, Express and Tit Bits in late 1899 the British public had watched with fascination and a growing sense of foreboding at the unfolding of yet another war in South Africa.

Within days of declaring war the Boers had encircled the diamond town of Kimberly, trapping Cecil Rhodes, then besieged Baden Powell and his army in Mafeking before attacking Ladysmith, ensnaring over 10,000 troops within its confines. Totally unprepared for the Boer offensive the British then suffered a string of setbacks in the late autumn of 1899, culminating in what became known as Black Week. In the humiliating defeats between the 10th and 17th of December of Stormberg, Magesfontein and Colenso, close on 3,000 British soldiers were either killed, wounded or taken prisoner. In the eyes of the British public the Boers were characterised as the aggressors, threatening the stability of the Empire and even that of England itself. The defeat of the Boers was therefore portrayed as nothing less than the defence of the realm.

To redress this humiliation and to bolster the forces, appeals were sent out to all the colonies for volunteers. Of special importance was the need for mounted infantry to track and counter the fast moving, horse riding Boers. On Christmas Eve 1899 a recruitment drive was launched, under Royal Warrant, for Yeoman Regiments to be raised on a county basis across Britain and Ireland, appealing equally to both patriotic spirit and a sense of adventure.

Qualifications: Candidates to be from 20 to 35 years of age, and of good character. 2

Officers and men will bring their own horses, 3 clothing, saddlery and accoutrements. Arms, ammunition, camp equipment and transport will be provided by the government.

The men to be dressed in Norfolk jackets, of woollen material of neutral colour, breeches and gaiters, lace boots, and felt hats. Strict uniformity of pattern will not be insisted on.

The term of enlistment for officers and men will be for one year, or not less than the period of the war.

Volunteers or civilian candidates must satisfy the Colonel of the regiment that they are good riders and marksmen, according to the Yeomanry standard. 4

Moving to the Long Valley Riding School in Aldershot Campbell spent four weeks in intensive training. As he was to be deployed in the role of Scout and Despatch Rider, there was a strong emphasis on horse riding skills and signalling in addition to the hand to hand combat training in sword, lance and bayonet – training that included, “tilting, lemon cutting, heads and posts etc.” 6

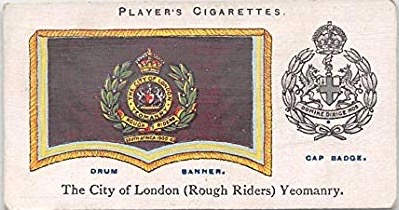

By early March Campbell had been enrolled as a “Rough Rider”. His Battalion was officially called the City of London Imperial Yeomanry and many of its recruits were men of means with family connections, who were prepared to take non commissioned roles to serve their country and seek a bit of adventure. Their main patron was Major the Earl of Latham and the volunteers soon came to be known as Lord Latham’s “Rough Riders”. The battalion was divided into four companies, each of about 120 men.

“The original contingents of the I.Y. were an amazing collection of individuals who were generally socially superior to the men of the regular army they were meant to serve alongside. The 47th Company (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) consisted almost totally of gentlemen from the City of London who not only gave their wages over to the Imperial War Fund but were willing to pay for a horse, their equipment and passage to South Africa. There was also Paget’s Horse which was recruited through gentleman’s clubs, in total over 50% of the original contingent were of middle and upper classes.” 4

He spent the first couple of weeks in London organising his uniform – khaki serge jacket, Bedford cord breeches, brown field boots, spurs and a heavy overcoat, together with his military equipment which consisted of rifle, bayonet, belt and bandolier. 5

What had become known as “Black Week” before Christmas 1899 was indeed a bad week for the British public, but it was a worse week for Chamberlain’s government and the prestige of the Empire. To have the might of the 21,000 troops of the most modern and sophisticated army in the world defeated by an irregular force of 8,000 Boer farmers was not a message that the largest empire the world had ever known would wish to convey.

What the Boers had on their side were mobility and motivation – the Boers were fighting to preserve their livelihoods – and they presented the British with an unusual military paradox. The British were trained to fight to the last man and expected to give their lives for King and Country 5 and had a seemingly inexhaustible supply of troops from the Indian subcontinent who could be ordered into battle against the Boer machine guns. The Boers, when the odds were stacked against them, merely melted away by night, preferring to live to fight another day than die for someone else’s cause. It was in essence a twentieth century guerrilla force outwitting and outmanoeuvring a 19th century imperial army. 7

Weakness was not a signal the British wished to portray particularly in potentially unstable outposts of the Empire such as India or Sudan. Still less did they wish any show of vulnerability in the political ferment closer to home in Ireland, where pro Boer rallies were taking place in towns across the country. In Dublin for example mounted police baton-charged a crowd of 20,000 pro-Boer demonstrators in the worst unrest for a hundred years.8

While colonial self government had been granted in other British colonies, the Tory government was reluctant to offer the same autonomy to Ireland “for reasons of security”. 9 After the defeat of two Home Rule Bills Irish nationalists were becoming increasingly frustrated at being denied sovereignty of their own country and were turning to new friends, enemies of the crown, in support of their cause.

Not everyone in Britain was in support of the war effort either. One group who risked the ire of the British public and suffered vilification and calumny were the Society of Friends. Prominent Quakers, among them Joshua Rowntree and his sister Maria 10, were vocal in their opposition to the war, establishing The Friends of South African Relief Committee. Joshua, a Liberal MP, was a hugely influential member of the Quaker community. His sister, Maria, was married to John Ellis, also a Liberal MP and grandson of John Ellis (referred to in the early post ‘Bukom to Burton’) philanthropist, abolitionist and railway pioneer – and brother of Joseph Ellis, great great grandfather of Polly Hart, who was married to Campbell’s son David. Campbell’s daughter, Feo, was married to Cyril who was brother-in-law to Colin Ellis, Polly’s father. (Work that one out!)

On 14th April, after their four weeks of training in Aldershot, Campbell’s company boarded the train for Southampton along with the 72nd, 76th and 78th which made up the full complement of 500 men of the XXth Battalion of Rough Riders, where they embarked the SS Canada for South Africa.

Click on the link to view the Parade of the Imperial Yeomanry that I have put together from rare Pathe News footage.

References

1. Lord Longford, the 4th Earl of Longford, was an Irish peer and soldier. His son, Frank (1st Baron Pakenham) was a British labour politician and social reformer. His grandson, Thomas Pakenham was a journalist and historian and wrote The Boer War, 1979, referred to in these posts.

2. There is no doubt that Campbell was of good character, but his age is certainly inquestion. He was 20 on the 24th February 1900, but on his enlistment paper on the 19th March he states his age as 23 1/2, giving himself the benefit of 3 years. Possibly this was to compensate for his youthful “fresh complexion and 5’5” height” as described on his papers.

3. As it turned out only the officers brought their own horses. The Troopers were supplied with Hungarian cobs when they arrived in Cape Town.

4. https://www.angloboerwar.com

5. Records of the Rough Riders Imperial Battalion Imperial Boer

Anglo Boer War – Imperial Yeomanry: https://www.angloboerwar.com/unitinformation/imperial-yeomanry-by-company/1946-imperial-yeomanry?showall=1&limitstart=

South African Military History Society – Journal – THE IMPERIAL YEOMANRY – PartOne – 1900 http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol136sw.html

Gentlemen’s Military Interest Club: The 1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders) http://gmic.co.uk/topic/23715-the-1st-city-of-london-yeomanry-rough-riders/

also: XXth Battalion Imperial Yeomanry

Captain G McKenzie Kew, Brown & Wilson, Bedford 1907

Reprint: Forgotten Books 2012

General Sir Ian Hamilton’s speech in which he shamelessly misrepresents theintentions behind the quotations from both Blake and Browning at thecommemorative service in Waltham Abbey in memory of Rough Riders fallen in theBoer War.

“…to show our affectionate remembrance of those brave Rough Riders who will rideno more… who came forward as free Englishmen willing to risk their lives in defenceof their native land.”

“ If foreign nations could only be made to realise that there are hundreds ofthousands of young Englishmen who are prepared, in case of need, freely to “ spendtheir sweet lives to do their country servic “Then shall English verdure shoot….anddreary war shall be no more” (Blake)

He continues, “ Life’s highest point is reached in the display of heroism…and he is ahero if he is willing to lay down his life for his native land.. . May many a boy and girl,whilst gazing at (this memorial) be filled at the same time with a burning patriotismand unquestionable desire to emulate their deeds, for those who are here enshrinedhave died to love of England, love of duty, love of heroic daring. They have indeednobly proved by their glorious end the truth of those great words:- “Love is all andDeath is naught.” (Browning)

6. See newspaper article below

7. Anglo Boer War Podcast Des Latham

THE BRITISH ARMY AND THE SECOND BOER WAR – https://

battlefieldanomalies.com/2boerwar/

8. https://comeheretome.com/2015/12/26/a-riot-on-college-green-1899/

also: Forgotten Protest Ireland and the Boer War Donal P McCracken

also: MacBride’s Brigade in the Anglo-Boer War https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/macbrides-brigade-in-the-anglo-boer-war/ «A Fellowship of Disaffection » : Irish-South African Relations from the Anglo-Boer War to the Pretoriastroika 1902-1991 – Persée https://www.persee.fr/doc/irlan_0183-973x_1992_num_17_2_1086

9. Reason of National security

10. Joshua Rowntree was an old boy of Bootham school, a Quaker school in York renowned for nurturing the Quaker ethos and where generations of the Ellis family were educated.

11. Video Credits:

Goodbye Dolly Gray – Harry MacDonough – British Boer War Patriotic Song

Videos: Rare War Footage from The Boer War (1899) | War Archives – YouTube

Boer War Material Reel 1 (1899-1900) – YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yjD8ofAfd4

General Reading Sources:

The Boer War, Thomas Packendem

CommandoA Boer Journal of the Boer War, Deneys Reitz,

A People’s History of Britain,Rebecca Fraser