Off to War (Part 2)

After a five day voyage the Canada arrived at Las Palmas in the Canary Islands. Any expectations of a lively bit of shore leave were quickly dampened by the naval officer who came aboard, and orders were given for immediate departure. While they were preparing to leave a homeward bound transport from the Cape, the Austral, passed close by. She was carrying sick and wounded from Ladysmith and was greeted with “lusty cheers” from the greenhorns on board the Canada, to which there was but a feeble response from the Austral – possibly a foretaste of the shattered illusions of many such volunteers on returning transports over the coming months.

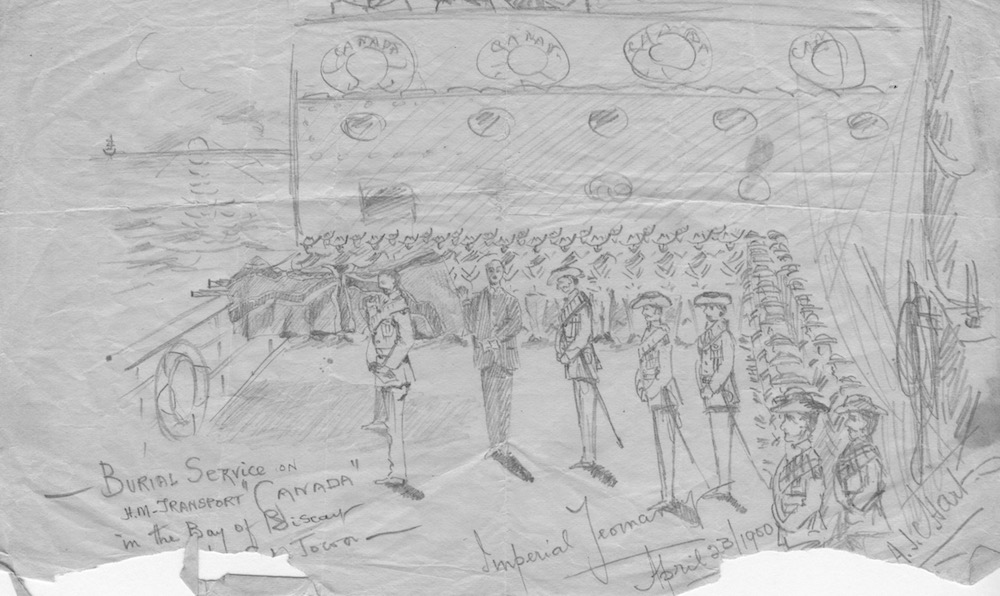

Three days after leaving Las Palmas while the Canada was off the Gold Coast, the first death of a Rough Rider took place. As Campbell sketched the ceremony from the quarterdeck Colonel Colvin read the Burial Service at Sea and three volleys were fired as the body of Trooper Moger of the 76th, who had died of pneumonia, was lowered to the ocean to the strains of the Last Post.1

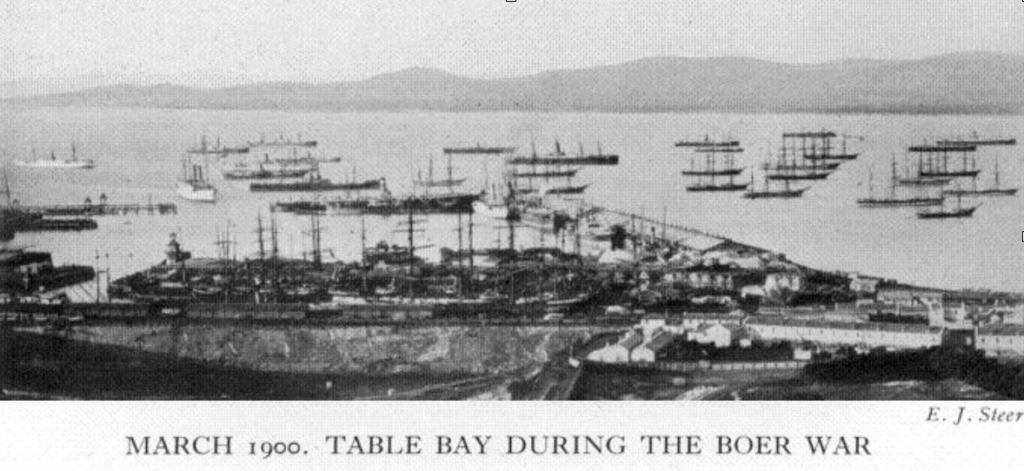

After a further two weeks at sea early on the morning of May 3rd the misty shadow of Table mountain appeared against the vivid purple skyline. Below it berthed, moored and anchored in Table Bay was a vast fleet warships, transports and merchantmen. Disembarking were new recruits from all over the Empire, volunteers who had heeded the call from Canada and Australia alongside regiments of sepoys from the (British) Indian army and infantry regiments from England. These troop reinforcements were all part of General Robert’s new offensive. Having replaced the blundering Redvers Buller as head of the army Roberts was assembling a force that would ultimately reach a total of 600,000 troops in order to defeat an enemy that was never more than 80,000. With the eyes of the world on him Roberts was taking no chances with British prestige.

With no room to berth, the Canada lay at anchor all day. Campbell and his fellow crew members soaked up the magnificence of the location, dominated by Table Mountain, ‘enveloped in a clammy white mist which gradually lifted until it finally rested on the top forming what is locally known as The Cloth’.2 Some were probably reflecting on what was in store for them and their future role in the war. Few questioned Britain’s moral right to rule South Africa and there was no sympathy here for the enemy – the Boers of the Orange Free State and Transvaal whom they considered the belligerents in the war. Few asked what the Dutch or English were even doing here in the first place, or why the black natives, whom they referred to as “kaffirs”, were subjected to subservient roles by both white races.

In fact the Dutch had originally arrived in the Cape as far back as 1652. Funded by the burghers of Amsterdam the Dutch East India Company had been developing trading partners and shipping stations in the Far East and the Cape was a convenient supply port en route. Later during a series of European pogroms the Cape became a refuge for Dutch Calvinists, German Protestants and French Huguenots fleeing oppression and persecution in the own lands. These religious refugees brought with them a self reliant independence of spirit and an inherent distrust of European powers. The British took permanent possession of the Cape during the Napoleonic Wars, needing the security of naval bases to counter the French threat from the harbours of the Seychelles and Mauritius, securing its trade route between Britain, the Far East and Australia.

While relations between the ethnic groups under British rule were relatively harmonious in 1834 a far reaching law was enacted across the whole of the British Empire which was to have devastating consequences for the Boer population. While slavery had been abolished in Britain in 1807 vast numbers of British citizens continued to profit from its practice in the colonies. Many were owners or part owners or shareholders in colonial ventures dependent of slave labour. Shamed into abolishing slavery in the colonies the British government was forced to recompense slave owners on a per capita basis in order to ensure compliance. (No such compensation was offered to the freed slaves, most of whom were forced to take up employment with their former owners and masters).3

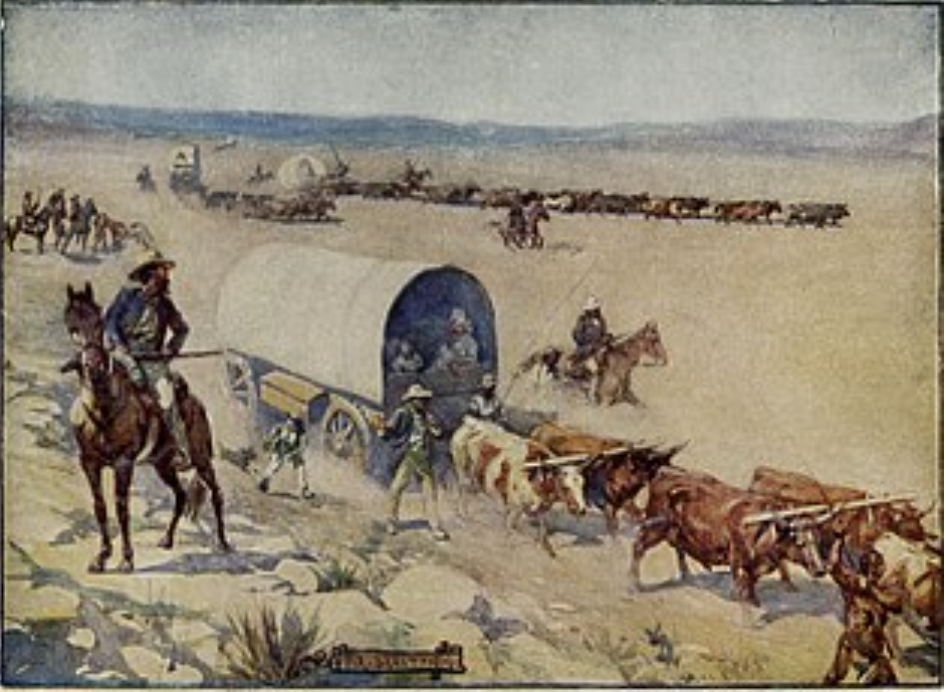

As subjects of the Crown colony, this same law applied equally to the slave owning Boers, but in order to receive their compensation it was necessary to travel to London to lodge their claim, a journey few were either prepared, or could afford, to make. While they may have bickered and quarrelled among themselves over some of their finer theological interpretations they were unanimous in agreement on one thing – that no one was going to tell them how they should treat their “kaffirs”. Consequently between 1835 and 1837 up to 5,000 Boers left the Cape on a great Trek, accompanied by hundreds of wagons and oxen and thousands of cattle, to establish a homeland outside of the remit of British rule.

Concentrating their settlements in the Natal area they established their own independent state, with a political and legal system that was deeply rooted in their Calvinist faith. By 1854 Britain had recognised both the Orange Free State and the Transvaal as independent republics, but that was before the discovery of diamonds near the Vaal river. Reconsidering their generosity the British then proffered the example of Canada as a successful model for a federation of South African States (and in the process gain control over the diamond mines). Neither Paul Kruger, the Transvaal president, nor Cetshwayo the Zulu king, were moved to accept the offer. In the case of the Zulus this led to their defeat by the British in the battles of Rorke’s Drift and Ulundi and the permanent loss of Zulu dominance over the region. The Boers responded with a rebellion against the British in 1881 in a military campaign that became known later as the First Anglo Boer War.

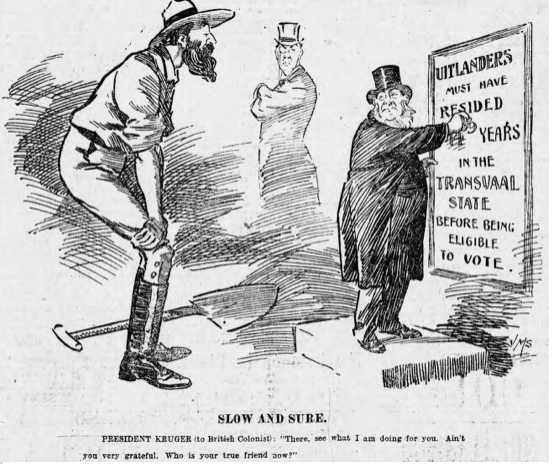

The seeds of the Second Anglo Boer War, the war in which Campbell was about to become embroiled, were sown in the footfall of the largely European prospectors and investors who poured into the Transvaal during the Witwaterstrand Gold Rush in 1886. Considered “Uitlanders” by the Boers, like the blacks they were denied any political representation – a practical move of self survival for the Boers who felt their unique theocratic lifestyle would be compromised if they were outnumbered by Uitlanders. Riding in to the defence of democracy the British Cape Colony first unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Johannesburg government in the shambolic Jameson Raid, then in more measured and cynical diplomatic moves manoeuvred the Boers into issuing an ultimatum with which the British had no intention of complying. Thus painted into a corner from which they could only escape by declaring war on the Cape Colony, the Boers handed the British the justification they needed to invade the Boer states and in the process take over the largest goldmines in the world.

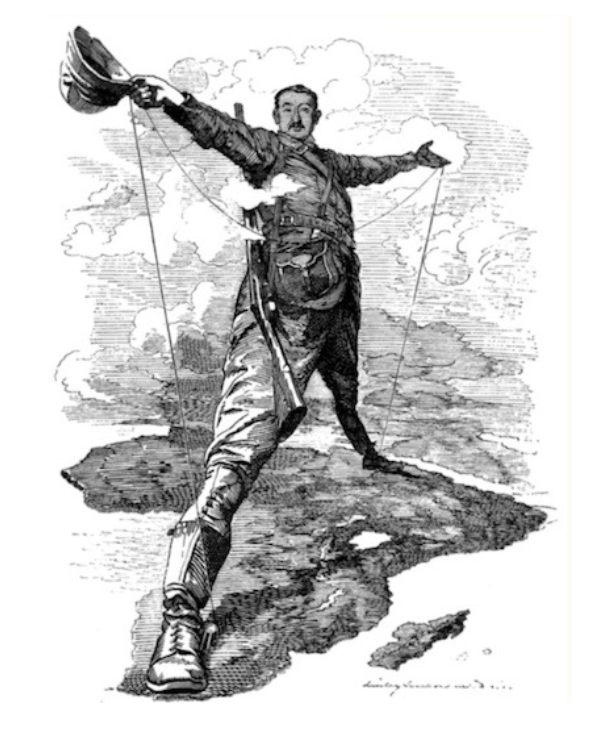

Pulling the strings for the British interest was the Cape Colony Prime Minister and diamond magnate, Cecil Rhodes. Rhodes’ ambitions for the Boer colonies were no secret. Five year’s previously he had attempted to engineer a putsch in Johannesburg through the failed Jameson Raid. He had already effectively annexed Rhodesia, ostensibly for the Crown, through his Chartered Company, the British South Africa Company. In fact his ambitions were a good deal less modest than just the takeover of a couple of Boer republics – his dream was for a British Imperial Africa and he intended realising it through the construction of an Imperial Railway that would run from the Cape to Cairo. The obstacles of its having to pass through French and Portuguese territory along its way were bridges he was quite prepared to cross when he arrived at them. 4

The Canada was gently tugged into the dock on May 4th and the following morning, Campbell and his fellow troopers began their orderly disembarkation for the start of their South African adventure. Twenty year old Campbell was about to play his part in the Second Anglo Boer War! 5